Bernard-Henri Lévy at the Foundation Maeght

By Andrea Longini

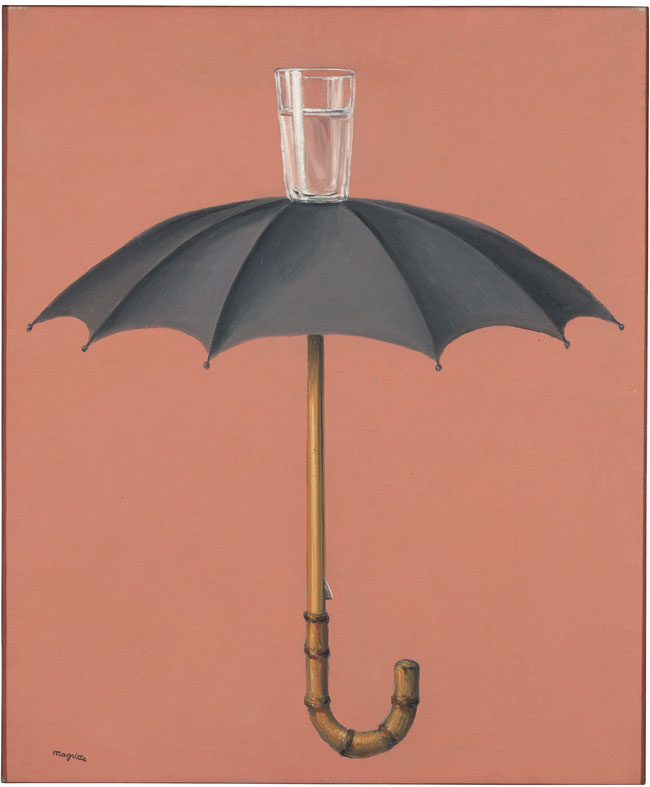

René Magritte, Les vacances de Hegel, 1959. Huile sur toile, 60 x 50 cm. Collection de M. et Mme Wilbur Ross – © Adagp, Paris 2013

René Magritte, Les vacances de Hegel, 1959. Huile sur toile, 60 x 50 cm. Collection de M. et Mme Wilbur Ross – © Adagp, Paris 2013

Bernard-Henri Lévy, author of American Vertigo and superstar philosopher in his native country, has curated an exhibit for the Fondation Maeght in southern France. “Adventures of the Truth: A Narrative” explores the relationship of art to philosophy over the last six centuries.

The exhibit, expansive in its inclusion of over 120 pieces, features seven sequences that narrate a battle between philosophers and artists over whose privilege it is to portray the truth. Work by Jean-Michel Basquiat has found its way into the exhibit, as has work by Marina Abramović, Anselm Kiefer, and Ellsworth Kelly.

The exhibit opens with a challenge. The first sequence, entitled, “The Fate of the Shadows,” establishes that art laid in the shadow of philosophy, its alleged predecessor in representing truth. Here the viewer is presented with a panoply of works that seek to challenge common perceptions about what art should do: a lesser-known Warhol is featured as well as an incandescent work, “Poetry of Form” by Mike Kelley. Kelley’s black and white photographs of cave interiors are given whimsical titles which cleverly provoke the viewer into associating two seemingly dissimilar cues; for instance, a hippopotamus and a rock. It is compelling pieces like this one that give the exhibit its soul; without them, the sheer number of works can imply a hodge-podge.

Pierre et Gilles, Sainte Véronique, 2013 (modèle: Anna Mougladis). Photographie peinte – pièce unique encadrée par les artistes, 100 x 70 cm – © Pierre et Gilles

Pierre et Gilles, Sainte Véronique, 2013 (modèle: Anna Mougladis). Photographie peinte – pièce unique encadrée par les artistes, 100 x 70 cm – © Pierre et Gilles

Next, the sequence entitled, “The Strategy of the Coup d’Etat” argues that one can indeed pinpoint the first awakening of art’s desire to portray truth over decoration: the Sudarium of Veronica, a Catholic legend depicted in painting as early as the 15th century where the image of Jesus appeared on a maiden’s handkerchief. Here, Lévy explains, artists realized if an image could be the incarnation of divine truth, then artists as well as philosophers could possess and portray it.

A rejoinder to that argument is presented in the following sequence, in a series of video interviews filmed by Lévy himself in which contemporary writers and intellectuals read thought-provoking historical texts to the camera. In these moments, philosophy in its distilled form is a powerful means of conveying what we understand to be reality and thought. The narrative continues on from there to Nietzsche references, abstract expressionism, and postmodernism.

Jacques Martinez, Triomphe de la philosophie, 2013. Technique mixte, 249 x 270 x 130 cm. Collection de l’artiste – © Photo François Fernandez / Droits réservés

Jacques Martinez, Triomphe de la philosophie, 2013. Technique mixte, 249 x 270 x 130 cm. Collection de l’artiste – © Photo François Fernandez / Droits réservés

“Adventures of the Truth” conveys a populist understanding of truth, philosophically: either you have it, or you don’t. One weakness of the exhibit is that it assumes that the viewer will take for granted the notion of an ongoing war between philosophers and artists. As noted by Digby Warde-Aldam, this is a perspective that may be challenging for contemporary viewers – especially English-speaking ones – to accept. There is little evidence presented to substantiate the claim of philosophy having preceded or superceded art. Instead, the viewer is met with an abundance of art and a dearth of philosophy. Since when is art not a statement of philosophy? The intimation is perplexing. And even if the exhibition isn’t suggesting that one must pick one or the other – philosophy or art – it seems at least to gesture at a nationalistic cultural divide: France, at least, seems to prioritize philosophy. (Philosophy is given short shrift in American schools while in France it’s a mandatory subject to pass the baccalaureat.)

Moreover, who is to say that the truth-teller is not art, has not been art for many years? Wallace Stevens noted that “the aim, in fact, of an artist should be, not to create as beautifully as possible, but to tell as much of the truth as is compatible with creating beautifully.” Philosophy is not able to unite beauty and truth as easily. However, it does not mean that “Adventures of the Truth” does not represent philosophy’s enduring influence in truth-telling or propose the disturbing notion that perhaps art attempting to depict truth is a more recent development than we may have thought. Yet the idea goes back at least three quarters of a century. Indeed, we were told by Jacques Maritain, himself a French philosopher, in 1937:

“Bernard-Henri Lévy, curator of the current Fondation Maeght exhibit, guides companions through the exposition” [July 25, 2013]

“Bernard-Henri Lévy, curator of the current Fondation Maeght exhibit, guides companions through the exposition” [July 25, 2013]

“It is less difficult for the philosopher than for the artist to be in disagreement with his period. There is little parallel between the two cases. The one pours his spirit into a creative work, the other ponders on the real with the understanding mind. It is in the first case by depending on the intellect of his time and pressing it to the limit, in the concentration of all his languor and all his fire, that the artist has a chance of reshaping the whole mass[.]”1

Ultimately, Lévy’s narrative nods towards the possibility that art stands on equal ground with philosophy. In the last sequence, the exhibit concludes with the notion that the two fields are now intertwined and feed off of each other. Collaboration wins. But it is up to the viewer to decide if they were ever really at odds in the first place.

“Adventures of Truth: A Narrative” runs at the Fondation Maeght in St. Paul de Vence through November 11.

==

1. Jacques Maritain, The Degrees of Knowledge, trans. Bernard Wall and Margot R. Adamson (London: G. Bles, Centenary Press, 1937), p. 4.

You must log in to post a comment.