David Lynch and Mathematics at the Fondation Cartier by Hattie Middleditch

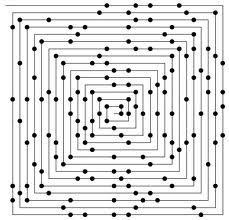

Ulam’s spiral, presented in The Room of the Four Mysteries in the central demi-sphere as part of a film by Beatriz Milhazes.

Mathematics: A Beautiful Elsewhere brings together the work of mathematicians, scientists and artists to transform abstract theories of mathematics into a nearly-hallucinatory experience. This latest exhibit at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, is designed to offer its visitors a ‘sudden change of scenery’. Though the ideas generated by certain pieces in this exhibition are somewhat inaccessible, this remains a fascinating exploration of the mystery and the beauty of mathematics.

Mystery is perpetuated not only within the pieces and puzzles themselves, many of which are initially impenetrable to the mathematically untrained. It also lies more fundamentally within the very essence of the subject under examination. The message runs clear throughout: mathematics is in itself a mystery, the truth of which may never be attained.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, ‘Surface of Revolution with constant negative curvature’, 2008.

The exhibition starts with the Library of Mysteries, housed in a zero-shaped structure. The focus of this space is an audiovisual installation put together by David Lynch which presents a collection of books selected by Misha Gromov for their importance in the history of mathematics and of human thought in general. Quotations from the titles are also projected onto a screen, each a musing on how the human mind encounters, and rationalizes their surroundings.

The library ranges from Heraclite’s Fragments, written around the 6th century B.C., to Alexandre Grothendieck’s Récoltes et Semailles. A quotation from the latter work talks of the ‘going back and forth between the apprehension of things and the expression of what is apprehended’. This goes to the heart of what many contributors to this exhibition seem to believe mathematics is about. It is a way of apprehending our exterior world and simultaneously a means of expressing, via mathematical structures, that which we have apprehended.

David Lynch, ‘Universe coming from Zero’. Animated film projected onto the ceiling of the Library of Mysteries.

The Joy of Math, a film by Raymond Depardon and Claudine Nougaret also deals with this idea. Mathematicians involved in the creation of the exhibition are able to express themselves in their own words. Sir Michael Atiyah talks of how our exterior visions and pictures reflect the exterior world yet are entirely different. In mathematics, where ideas are most fluid, this means the interpretation of the outside world through the internal visions and structures which the mathematician has created or gained from experience. What makes maths special in the creation of these visions, according to Alain Connes, is that ideas can be transplanted between different fields. This is because mathematical structures exist in a number of parallel universes. Mathematics questions materialism as a naïve theory in that it reduces reality to material things. Reality in fact is so much more complex than this and it is through mathematics that we are able to conceive of it. The result is beyond exciting. Just like in Alice in Wonderland, Connes enthuses, you are lead to discoveries that you could never possibly have imagined.

Yet, as Atiyah emphasises, the mystery is far from solved. If the goals in human life are the search for truth or beauty then Atiyah recommends erring on the side of beauty. To him, beauty is a subjective quality. That which we personally see and understand to be beautiful is certain. Truth on the other hand is an unattainable goal: ‘we will disappear long before we reach the end of the road to mathematical truth’. The idea of mathematics as an infinite journey of discovery is examined also in the Room of the Four Mysteries in which text by Misha Gormov is interpreted by Patti Smith as an accompaniment to a number of visual installations.

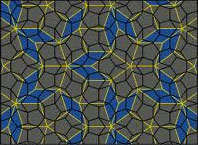

Penrose Tilings, presented in a film by Beatriz Milhazes projected in the central demi-sphere of The Room of the Four Mysteries. A giant collective of penrose tiling is also displayed on the wall of the space so that visitors can arrange two types of magnetic tiles.

The four mysteries of the world are outlined as: physical laws, life, the brain (‘an accidentally developed mass of organic matter’) and mathematical structure. Although everything we see has evolved under the influence of physical laws, these have not helped us to elucidate the structures of life. Mathematical models are the only way to represent any of these structures in a format which is comprehensible to the brain.

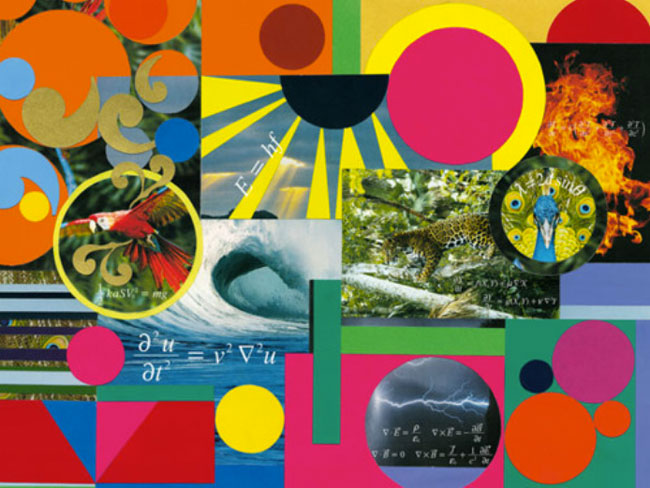

This idea is reinforced by Beatriz Milhazes’s collages displayed on the walls and in a central demi-sphere in the same room. The collages are a composition of landscapes and animals to which sets of equations have been added illustrating how natural phenomena can be displayed using mathematics. However, as Smith’s dialogue reminds us, mathematical structure is in itself a mystery: the puzzle of human life remains unsolved. The fact that Milhazes’s collage is entitled Paradise emphasises the fact that this is a perfection that has not – indeed, may never – be attained.

Penrose Tilings, presented in a film by Beatriz Milhazes projected in the central demi-sphere of The Room of the Four Mysteries. A giant collective of penrose tiling is also displayed on the wall of the space so that visitors can arrange two types of magnetic tiles.

You must log in to post a comment.