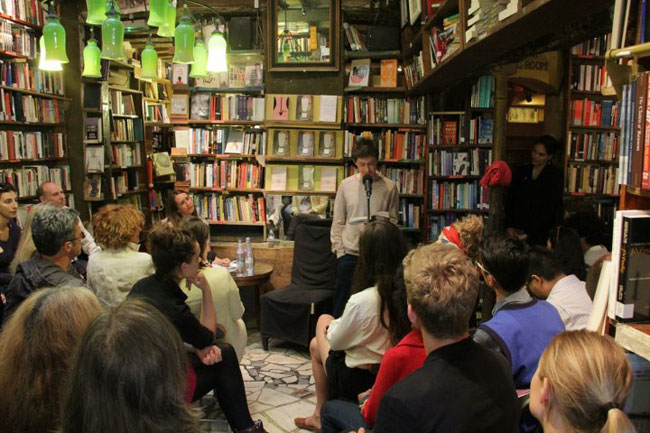

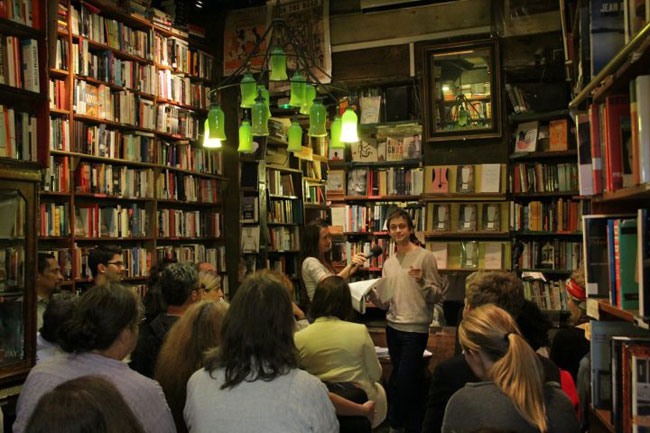

Adam Thirlwell goes 'Kapow!' at Shakespeare & Company

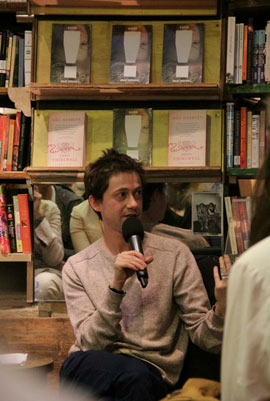

Adam Thirlwell came to Shakespeare and Company on Monday, June 18th, to read from his newest book, Kapow!, published by Visual Editions. The following interview is transcribed and edited from Adam’s conversation with Jemma Birrell, as well as the question and answer period following the reading.

Discussed: the trap of fiction; the unintended consequences of drinking; the importance of laundry vans; an unknown Cairo; the inherent authenticity of warts; and romance.

Her Royal Majesty will be publishing the interviews from Shakespeare & Company’s entire summer series, including the authors involved in NYU’s Summer Writing Program.

Jemma Birrell: Can you tell us all a bit about how this project started? Did you approach Visual Editions publishers, did they approach you? And how did it all come together?

Jemma Birrell: Can you tell us all a bit about how this project started? Did you approach Visual Editions publishers, did they approach you? And how did it all come together?

Adam Thirlwell: The first book Visual Editions published was a reissue of Tristram Shandy, which they sent to me (I think I must have written about it, and so they knew I loved it). So I went for a drink with them and within two or three drinks I had seem to have signed a contract to do a new book with them, which was not entirely my intention in having a drink. And they said this wonderful sentence: “there’s nothing you can ask us to do that we can’t do – you can’t think something too difficult.” So obviously that was a challenge that I wanted to try and meet.

I think a lot of it was I had this idea in my head that I was going to try to write the most digressive thing ever written.

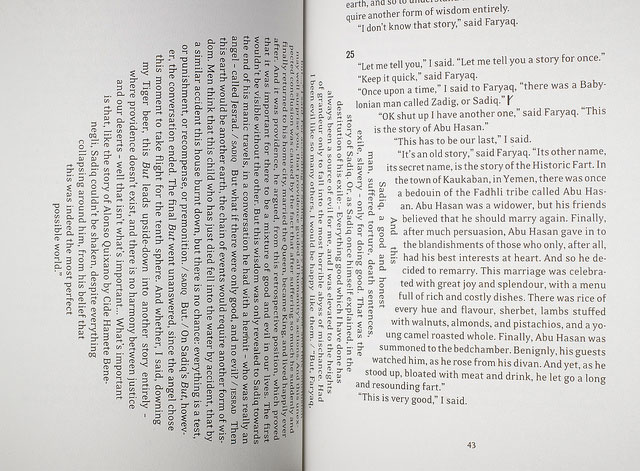

Visual Editions specializes in putting writers together with design studios, and they had just done this book by Jonathan Safran Foer, Tree of Codes, a book entirely made of holes. And so I don’t know if in some competitive way I wanted to do a book that was the opposite of holey, that was kind of expandy or something. And so the designs—basically I just wanted a design that would be readable with a million of these tiny digressions. It was the design studio that came up with various ideas, and the one they finished with was this idea that the text would go in different directions on the same page, and that if there was a digression that was so long, then it would somehow expand into a fold out.

JB: Were you thinking about which sentences would be those digression, as you were writing it? Or did this come after the fact?

AT: It was a bit of both. I definitely wrote as digressively as possible. Actually what happened was, at first VE gave me the templates where I actually did have word counts. I don’t know if people have seen their other books, but they’re actually obsessed by the idea that every book has to be the same height. So there was a page size that was unchangeable. And this therefore meant that because the design studio had chosen the font they liked, I was basically not in charge of this book at all. There was a certain word count to the page that I had to follow, and therefore they gave me various word counts of how long the digressions could be in relation to the page.

JB: Kind of Oulipian.

AT: Yes, it was actually quite easy to write. Easier because I was writing to this constraint. But at the same time I wasn’t entirely sure of exactly where it was going to happen. I think, when I was first writing it, I wasn’t sure if they would determine the digressions, or whether it would be me, and so in the end I ended up writing something even more digressive then I intended. I basically tried to make every sentence a digression in some way so that they could just happen anywhere.

The digressions were eventually settled on, I think mainly with what I thought should be the digressions. In the case, for instance, of the very long foldout, they had always wanted this idea that this book would get crazier and crazier. The visual digressions early on are relatively readable, and the idea was that the as narrator got more and more insanely caught up in the story, and the story within the story, the digressions would become even more upside-down and back-to-front, culminating in this point where the whole book falls apart, and nine pages fall out.

There were only four or five hours before the book went to print when we realized that there was now nine blank pages on the other side, which none of us had thought of. With five hours to go, I got phoned up with them saying we need a 563 word digression, and so I had to write that at the last minute. So it was a very weird collaboration.

JB: Why did you choose to write about this subject – the Arab Spring? I know in the book the narrator is interested as an outsider to look around it.

AT: Yes, there’s a point where the narrator, who is obviously just a cartoon version of me as normal, says ‘I’m half-Jewish and I’ve always had this desire to write an Arab novel.’ That idea of wanting to steal stuff that isn’t yours is definitely my main emotion in life. It was both a naughty kind of emotion of thinking why can’t one do something inauthentic as it were, why should writing always be based on something that you’ve lived personally, and also some sense that in fact these categories were wrong.

Then there’s this anxiety, long before the Arab Spring, the anxiety that a book should encompass all of world history. And while I think that’s a melodramatic anxiety, it’s certainly one that I still feel. And so I wanted to dramatize both the anxiety and the attempt to do it.

I was genuinely obsessed with the Arab Spring, and it felt like the right thing to do. I was very interested in this idea that you never understood the true story, that there was always an extra story behind the story you knew.

JB: Yes, because in addition to the writing of the revolution you are actually turning the book around [a physical revolution or rotation]. Within the story there are so many layers. It’s not only the story about the Arab Spring, there’s the love story, there’s the personal reflecting of the characters as well.

AT: Yes, and I think that was definitely my hope. That this idea of revolution would be explored in a million different ways, so that the story of a marriage becomes a story of counter-change. The revolution in some ways becomes this impediment, and the larger revolution stops the smaller revolution, but at the same time I was quite interested in questioning if one could say whether one was larger or one was smaller. The question of scale, which I’ve always been interested in writing about. Dismantling was part of the game of this. That’s when digressions became very useful because I could smuggle in some major historical world fact, or it could be some minute detail of the story.

JB: What is so digressive, in a way is also the humour. Obviously, you write—

JB: What is so digressive, in a way is also the humour. Obviously, you write—

AT: —I’m not very funny—

JB: —No, you’re a funny person, Adam. And that was really interesting as well. At one point in the book the narrator not being beholden to being serious, and being able to have fun with the subject and with the characters. And you get that in the novel.

AT: The level of the narrator is true. I always want to upset people by making jokes about things they take very seriously, and at the time of the Arab Spring one was definitely not supposed to find that amusing. So there was definitely that kind of mischief that I wanted to play with. But also I’ve always wanted to write about someone who loses their sense of humor, which seems to me to be an unexplored area of fiction, but something that happens to people, as far as I can see, all the time. And for millions of different reasons. And I think it’s a really interesting subject.

A lot of comedy, actually, is based on using people who no longer have a sense of humor and then subjecting them to terrible humiliations which, if they still had a sense of humor, they would find light and irrelevant, but instead they experience as tragedy. I wanted to explore what was comical in digression, because digression is always relativising in some way. It’s there in someone like James Joyce, where he’s always undercutting Stephen Daedalus’s big grand theories of literature. And then there will be a small detail about a laundry van going past. That structure of undercutting is something I’ve always liked playing with, so I suppose this was just the high-speed version of it.

JB: Another thing that I loved was the way you were speaking to the reader. Is this something that allows you to get closer to us? I know you’ve used that in your other works as well. Is it something you enjoy, that you feel quite attached to?

AT: I’ve discussed this with my therapist many times.

JB: It works really well, though, because you do feel this intimacy with the characters, you feel the narrator.

AT: It’s definitely a technique that I’ve used, I think, in all my books, and I think here almost more than normal. The book I’m writing now I’m trying deliberately not to address the reader. It’s strange. I don’t like absence of the reader, as it were. I’m always jealous of playwrights, writers who can go watch their play being performed, and they can see the audience react to it or not. The best you can do as a novelist is occasionally see someone read you on the metro, at which point you feel like a stalker and so you leave, and they often don’t stop.

Talking to the reader is definitely a kind of desperation, and an anxiety, and it’s tricky because sometimes it can actually—I think it is also, if I were honest, a slight vaunting of power. There’s a way in which it’s both a very accessible mode of writing, in that it’s trying to say and I think it’s sincerely saying, that writing is an address to the reader, a conversation. And at the same time it’s a one-sided conversation because the reader can’t talk back. The book that started all this was Tristram Shandy, and I think that’s a prime example of a narrator pretending to be nice by chatting to you but in fact the chat is absolutely a form of power.

So I don’t know.

It’s definitely way of also freeing myself to comment on the characters, a way to make the thing feel more realistic. If you’re talking to the reader, than the characters might be real too. An attempt to make everything on the same plane that I’ve always liked.

Q: You talk a lot about romance in your books, in Politics, and in your short story published in Granta, “The Cyrillic Alphabet,” which I found to be touchingly romantic. And so I was wondering how you feel about that. Do you consider yourself a romantic, are writers romantic by nature? Not necessarily in the lovey-dovey way.

AT: I do write a lot about romance, and the concept of romance. I don’t—oh that’s a horrible question…it’s true I’m very fascinated by romance, in different directions. I’m always interested in exaggeration of feeling, and trying to get feeling correct in descriptions. Romance is fascinating because it’s two things at once. Obviously there’s a truth to desire, a truth that desire creates, and at the same time it’s an exaggeration. Trying to be true to both the irony and the sincerity of it is something that interests me.

Oh, this is like therapy…

Q: You talk about detail of feeling, to amplify the notion of detail. Do you think there’s an ethical problem in writing about a time and a space that you don’t have direct access to? In so much detailing, is there an elusion of accuracy? For example, the setting of Kapow!…

AT: The setting was Cairo. But I did deliberately not name the place. That was for various reasons. One of them, precisely, to try to preserve this small area of pure imagination where it wouldn’t therefore be people saying “actually you can’t turn left on that street.”

Detail is a really fascinating thing. It’s the essence of a novel in some sense. The real interest for me in novels is not what people would call “realistic,” but how you make something convincing. The question of the convincing seems to be nothing to do with realistic or not, it’s whether you can somehow invent a world that feel coherent. It doesn’t necessarily have to correspond to the world other people are seeing, it purely has to be coherent on its own terms.

On the other hand, I sort of believe—and I don’t know if every writer must slightly believe this—that there is such a thing as a universal. Writing is often slightly at odds with theory. Where theory would say, you’re very much historicized and you’re very much in the moment and therefore you don’t have access barely to the person next to you, let alone something occurring in a completely different culture. And I think deep down I just can’t believe that.

There’s a passage I love in Diderot where, he suddenly breaks from a not very good story (it’s called “The Two Friends of Bourbonne”). And then suddenly there’s a little passage on the history of criticism which I’ve always loved where he basically starts defining what he calls the “historical tale”, what we’d call a realistic tale. And he simply says “All you need, if you look at a portrait, and it’s perfect, no one believes in it, but if you just add a wart, or a scar on their upper lip, immediately you know that they are real.” That seems to me to be true.

There’s a way—and this is the art of the novel, an art, a deep art—is inventing the details that convince. I don’t think there’s any reason why you shouldn’t be convincing. And I had fun with that in some of the digressions I read just there. I deliberately wanted the similes to be as far removed from the real context that I was describing. It was part of the game of saying “it doesn’t matter,” about that question of authenticity. So I compare a guy in Cairo, on the floor of an elevator, to a music stand in Detroit. That was deliberately trying to think of things as far removed as possible.

Q: In some of the Middle Eastern countries, they purposefully put in a flaw in the process of weaving a carpet, in order to give the carpet a soul.

AT: Yes. I’ve got so many flaws in this carpet, it is intensely soulful. But yeah, I think that’s a similar idea.

Q: Do you think at all about the stamina of the reader? For me, it would feel, if pages all of a sudden fell onto the floor, it’s like I just started this digression…I’ve made it all the way to the end, can I make it? Is it supposed to feel like wandering through Youtube, or like a note, an author’s note? Did you think about how we should take the digressions?

AT: It’s true that one of the things that was interesting about this book was that I was doing the writing in Microsoft Word, and I was just putting in bold bits that vaguely [digressed]. So, very easy for me to read. It was only when I was suddenly reading the galleys that I’d realized what I’d done. Or not what I’d done, but what this design studio had done.

I made them tone down quite a lot—I mean I would say this is about a third toned down from what they initially wanted, because I was very keen to make sure it was as readable as possible within the crazy constraints we’d invented. Hopefully the idea would be that you just kind of get used to it, that you’d get into a rhythm. The idea is that it speeds up. At the start, there’s no more than one a page, and they’re relatively simple, and it gradually gets wilder. So the nine page digression at the end, at that point, I suppose you’ve entirely lost it.

The point was that these are digressions, and I deliberately wanted that you could ignore all of them. You can read this and not look at any of these digressions. It was partly to compromise the reader. I like comprising readers very much. I like making them uncomfortable. And it was partly to make them think ‘Should I read or should I not, and why am I not, and why is this important, and should I be reading the whole thing.’ So it definitely wouldn’t bother me if you lost one digression.

Q: If this last book was such an unusual form, and Miss Herbert also was creating a form as it were, can you tell us a bit about this new book that you’re writing?

AT: The new one is going to be the most linear book I can manage. It’s just going to be pure plot. Pure plot is all I want.

You must log in to post a comment.